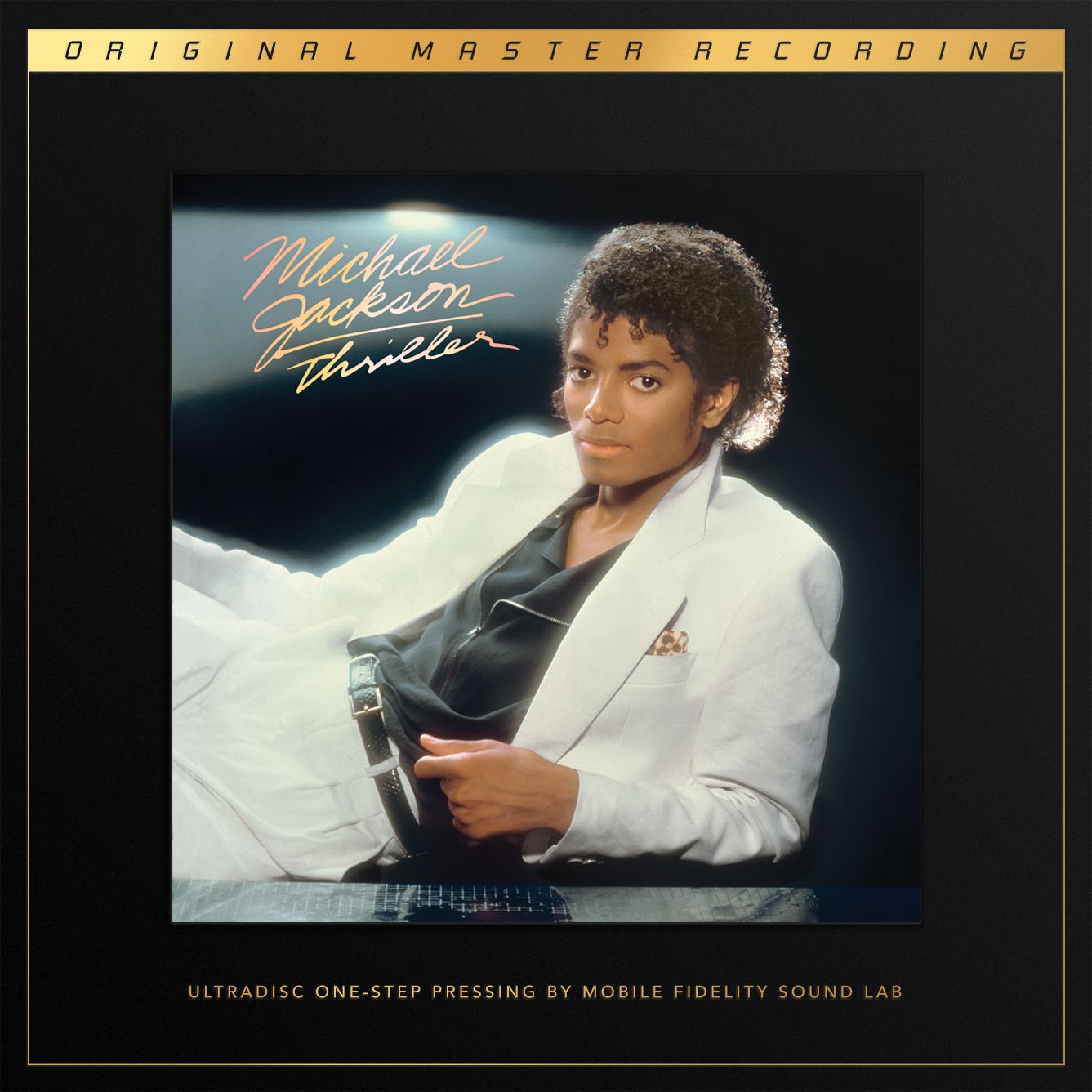

There probably isn’t a one of you who doesn’t own some version of Michael Jackson’s Thriller, which is, after all, the best-selling album of all time. Thirty-seven weeks at Number One on the Billboard Top LPs & Tapes chart, certified 38x platinum, a record-breaking eight Grammys including Album of the Year and Record of the Year (“Beat It”), the most Top Ten singles of any LP in history, not to mention the rocket-boost Jackson’s slick moon-walk videos gave to MTV’s popularity (and vice versa), Thriller changed things—not least, the public perception of Jackson himself, who went from a boy-band singer with boundless energy and a sweet falsetto voice to an international cultural icon. Once scorned by outfits like Rolling Stone, who feared putting Black musicians like him on its cover because “they don’t sell copies,” Jackson became the hottest thing in show biz.

In retrospect, a lot has been made about the “artistic change” in Jackson that Thriller represents. The redoubtable Stephen Erlewine of AllMusic rather captures the Zeit, writing that “although [Thriller] is an undeniably fun record, the paranoia is already creeping in, manifesting itself in the record’s two best songs: ‘Billie Jean,’ where a woman claims Michael is the father of her child, and the delirious ‘Wanna Be Startin’ Something,’ the freshest funk on the album, but the most claustrophobic, scariest track Jackson ever recorded [allmusic.com/ album/thriller-mw0000056882].”

I don’t know. Reading Michael Jackson’s psyche directly into his music strikes me as a classic instance of the biographical fallacy. Jackson was the quintessence of pop—a strange, lonely, tremendously gifted and canny artist with an unquenchable drive to be Number One and (with the help of arranger/producer Quincy Jones) an unfailing sense of what would work for him musically to achieve crossover success. In life, he may have suffered from an increasingly severe case of arrested development, but on LP it seems to me that songs like “Billie Jean” and “Wanna Be Startin’ Something” were less likely unconscious reflections of paranoia and more likely conscious attempts to comb more of the Jackson Five bubblegum out of his hair (a process that began with Off the Wall)—efforts aimed at making Jackson appear more grownup, macho, independent, and saleable, without sacrificing his boyish energy and charm. In Thriller, he got what he aimed for, and we got a uniformly delightful, irresistibly danceable album chockful of memorably catchy tunes.

Originally recorded, all-analog, by pioneering engineer Bruce Swedien at Westlake Recording Studios in Hollywood (April–November 1982) and mastered by none other than Bernie Grundman, the Epic Thriller won the Grammy for Best Engineered Recording and deserved it. Unlike so many pop albums that sound terrific on radio or TV but disappointing at home, Thriller has always sounded good on vinyl. A lot of this is owed to Swedien, who was famous for his innovative mic’ing techniques (he was, Michael Fremer told me, among the first recording engineers to use Blumlein pairs to record pop vocals and instrumentals, like those of Jackson and his musicians on this disc), some to Westlake Recording, whose studios were acoustically treated for flat frequency response and controlled reverb, some to Grundman, who has overseen the production of an extraordinary number of wonderful-sounding albums, but most to Jackson himself and to Quincy Jones, whose joint arrangements, choice of backup performers, and performances are, well, phenomenal.

For this 40th Anniversary reissue, MoFi claims to have used the original ½”/30ips mastertape, copied to DSD256, mastered at its analog console (with Tim de Paravicini electronics), and inscribed on a lacquer that is plated with a layer of metal, which, when peeled off, becomes the stamper (bypassing the lossy metal mother/father steps of conventional pressings). Belatedly, MoFi is now admitting to the DSD “digital step” in its LP-making process; indeed, the entire manufacturing sequence is now printed on a sticker attached to the front cover of Thriller—like the old SPARS code on LPs and CDs.

You can tell how MoFi’s Thriller is going to sound from the very first moments of “Beat It” on Side Two. The “ch’k” of the hi-hat is much clearer and less forward and aggressive on the MoFi than it is on the Epic LP. Indeed, every instrument and vocal on “Beat It” (on all the songs from Thriller) is clearer and cleaner and somewhat more laid-back, which is to say noise has been lowered substantially, and clarity has been raised substantially. As a result, the decipherability of lyrics, the contributions of backup musicians (like lead guitarist Eddie Van Halen and rhythm guitarist Steve Lukather), the overall neutrality of timbre and resolution of detail (such as the heightened breathiness of Jackson’s voice, which takes on a kind of see-through transparency that makes him sound quite “there”) are greatly increased.

So…a big step forward, right?

Well, yes and no. If you turn the page (or move the stylus) to the second cut on Side Two, “Billie Jean,” you’ll begin to understand the “and no” part. All the improvements in clarity, noise, resolution, and neutrality are still there, of course, but so is something else that is equally apparent on “Beat It.” Just listen to Ndugu Chancler’s big drum strikes followed by Louis Johnson’s Yamaha bass ostinato at the start of “Billie Jean.” Swedien wanted these drumbeats to stand out and went so far as to construct a plywood platform for Chancler’s kit, “ordering a custom-made bass drum cover, using everything from cinder blocks to specially designed isolation flaps, all to capture just the right imaging…‘See if you can think of any other piece of music where you can hear the first three drumbeats and know what the song is,’ Swedien [once] said. ‘That’s what I call sonic personality’ [Blender: The Ultimate Guide to Music and More, October 2005].”

On the Epic LP, that “sonic personality” is unmistakable. Putting aside the fact that “Billie Jean” (and every other cut on the album) is mastered at a much higher level on the Epic LP than it is on the MoFi reissue, the first strike of the drum hits hard enough to knock you back a bit in your seat. It’s got lifelike body, presence, and, above all, transient impact. So does Johnson’s Yamaha bass (which was especially chosen for its tone by Jackson, after Johnson demo’d every other bass guitar in his arsenal).

On the MoFi reissue, the drum and bass guitar are clearer with greater separation, detail, low-end extension, and more neutral and natural color, all right. But they are also less present and exciting. It’s almost as if some of the fun has been let out of the room. The upfront presence and thrilling power-range/midband impact of vocals and instrumental transients—and thrilling is the way the musicians, the producer, and the recording and the mastering engineers intended them to sound—are somewhat reduced.

Though I’ve been avoiding the question, I’m sure you’re wondering (as I did) whether these sonic differences are the results of the “digital step” MoFi is now taking in mastering. When it comes to this LP’s lower noise and higher resolution, they probably are; however, they are certainly also the result of the different EQ that MoFi’s engineers used on this reissue (for which, see the sidebar).

When it comes to mastering you can, I suppose, make an argument on behalf of any procedure that either: 1) makes the music sound more faithful to what is recorded on the tape; 2) more faithful to the sound of a live performance; 3) more faithful to the artists’ intentions; or 4) just more fun to listen to. This reissue rather falls into the first category, the original into the third and fourth. MoFi’s John Wood, Krieg Wunderlich, and Shawn R. Britton have taken an eminently enjoyable recording intended to be pure toe-tapping entertainment and turned it into something that demands and repays close listening—an audiophile recording rather than an exuberant, highly produced, bandwidth-limited, 80s’ dance mix.

Four Questions about Thriller for the MoFi Mastering Staff

First, who did the mastering on Thriller? Did your staff consult with Bernie Grundman, or did your engineers rely on their own judgment and experience?

John Wood: Our mastering engineer Shawn R. Britton did the ½”/30ips analog master archival transfer to DSD 256 using our customized Studer deck and digital gear at Battery Studios in NY. Krieg Wunderlich did the LP mastering/cutting in our studios in Sebastopol, CA. All sound was approved by Sony and the Michael Jackson estate.

Second, how did your mastering engineers decide on EQ for Thriller? What was the procedure (i.e., was the sound of the DSD master used as the sole “standard of comparison” for the sound of the LP, or are choices for “sweetening” made by ear, by engineering notes from the original mastering session, or by cross-comparison with Grundman’s fully EQ’d production masters or with the tonal balance of the Epic LP)?

Krieg Wunderlich: When mastering a title, we will listen to original pressings, and if the original mastering engineer’s notes are available, we will certainly take what guidance we can from that information. Often our goals can be somewhat different from those of the original mastering engineer. For example, our records are pressed on the highest-quality vinyl, so there is little need to raise the quieter passages in order to mask the noise floor of the poor-quality vinyl of the 70s and 80s. Additionally, we don’t need to concern ourselves with how our records will sound on the radio or a cheap set of loudspeakers. Our goal is to bring to our customers as much detail and nuance as possible from the original two-track master to the final product.

Third, when your LPs are pressed, does anyone check for centering? (I ask this question because the Thriller I received was miscentered; for that matter, so were the early Epic pressings I compared it to.)

Shawn R. Britton: The R.I.A.A. dimensional characteristics for 33-1/3rpm phonograph records sets a runout specification of recording grooves relative to the center hole at 0.050″ maximum deviation. We checked multiple stamper sets, and while some pressings had a detectable amount of runout (eccentricity), they are well within the RIAA specification. The definitive way of checking centering is the lock-out groove at the end of the record. If the cartridge body appears to be stable during playback, then it is fine.

Fourth, you pressed this Thriller at 33rpm. Do you have any intention of releasing a “limited-edition,” two-LP, 45rpm set in the future?

John Wood: Yes. In the future.

Specs & Pricing

Type: 33rpm, Ultradisc One-Step LP

Pressing: UD1S 1-042 A18/B19

Price: $100

MOBILE FIDELITY SOUND LABS, INC.

811 W. Bryn Mawr Ave.

Chicago, IL 60660

mofi.com

Tags: MOBILE FIDELITY MUSIC ROCK

By Jonathan Valin

I’ve been a creative writer for most of life. Throughout the 80s and 90s, I wrote eleven novels and many stories—some of which were nominated for (and won) prizes, one of which was made into a not-very-good movie by Paramount, and all of which are still available hardbound and via download on Amazon. At the same time I taught creative writing at a couple of universities and worked brief stints in Hollywood. It looked as if teaching and writing more novels, stories, reviews, and scripts was going to be my life. Then HP called me up out of the blue, and everything changed. I’ve told this story several times, but it’s worth repeating because the second half of my life hinged on it. I’d been an audiophile since I was in my mid-teens, and did all the things a young audiophile did back then, buying what I could afford (mainly on the used market), hanging with audiophile friends almost exclusively, and poring over J. Gordon Holt’s Stereophile and Harry Pearson’s Absolute Sound. Come the early 90s, I took a year and a half off from writing my next novel and, music lover that I was, researched and wrote a book (now out of print) about my favorite classical records on the RCA label. Somehow Harry found out about that book (The RCA Bible), got my phone number (which was unlisted, so to this day I don’t know how he unearthed it), and called. Since I’d been reading him since I was a kid, I was shocked. “I feel like I’m talking to God,” I told him. “No,” said he, in that deep rumbling voice of his, “God is talking to you.” I laughed, of course. But in a way it worked out to be true, since from almost that moment forward I’ve devoted my life to writing about audio and music—first for Harry at TAS, then for Fi (the magazine I founded alongside Wayne Garcia), and in the new millennium at TAS again, when HP hired me back after Fi folded. It’s been an odd and, for the most part, serendipitous career, in which things have simply come my way, like Harry’s phone call, without me planning for them. For better and worse I’ve just gone with them on instinct and my talent to spin words, which is as close to being musical as I come.

More articles from this editor

![Thriller 40th Anniversary Review [Mobile Fidelity]](https://www.theabsolutesound.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/11/Melody-GardotPhilippe-Powell-Entre-eux-deux-300x300.webp)