Those of you who have been reading me for the past 30 years already know that I am a huge fan of Magnepan loudspeakers. Indeed, as I’ve noted in these pages many times before, it was the Maggie 1U/D that set me on the road to the absolute sound. Before I heard that first Magneplanar, I relied on published specs and magazine test results to narrow down the speakers and electronics I was interested in. After listening to it (in 1973) and being momentarily fooled into thinking I was hearing someone playing a real concert grand (there happened to be a piano in the room, hidden behind what I thought were decorative screens, which turned out to be Magnepan 1Us), I realized there was a better way to judge high-fidelity components—the HP way, the TAS way, the way that puts the closest approximation of the sound of the real thing first and specs last.

Not only did Maggie’s founder, Jim Winey, invent an entirely new transducer that came closer to making acoustic instruments sound “there” than anything that preceded it; he also priced his flagship quite reasonably at $995 ($6550 in today’s dollars). To this day, Magnepan’s offerings are eminently affordable. Even its current highest-ticket item—the eight-foot wide, six-foot tall, four-panel MG30.7—comes in at $37,995, which isn’t chicken feed, of course, but is still a far cry from a three-quarter-of-a-million-dollar Magico M9 or a half-a-million-dollar Wilson XVX or a $320k MBL 101 X-treme MKII (which are the company it keeps).

When I reviewed the MG30.7, I explained in detail what I liked and didn’t like about Maggies. Rather than recasting what I wrote, allow me to quote from that review, starting with the plus side of the Maggie ledger.

“To begin with, Maggies have no box and, hence, no box coloration. Given the strides that have been made in dynamic drivers and their enclosures, you might think this wouldn’t make as dramatic a difference as it did years ago. But that really isn’t the case. Boxes, no matter how skillfully made, are still boxes, and to varying degrees they still add their own resonant colorations to the sound. (They also often add confusion to the sound, due in part to the turbulence of the backwaves that are rattling around inside them.) Typically, this results in a dark woody or bright metallic hue overlying the natural tonality of instruments, some elongation or truncation of the duration of the dynamic/harmonic envelope, a masking of fine detail, and an intermittent sense that the music can be traced back to the drivers—faults the Maggies simply don’t suffer from.

“Now I’ll grant that the sound of box speakers can often be very attractive—that the spring-like action of air trapped inside (or vented partly from within) their enclosures adds ‘zip’ to attacks, tonal density and dynamic weight to the upper bass and lower midrange, and slam to the midbass. Indeed, for those listeners who put beauty and excitement first, the added color and power of box speakers are indispensable. For listeners looking for an approximation of the sound of the real thing, however, these are colorations that one almost never hears in life, unless the orchestra itself is enclosed in a box (as a pit orchestra is) or its sound is being amplified by loudspeakers in a hall or an auditorium.

“Second, Maggies are dipole line-source rather than dynamic quasi-point-source loudspeakers. This means they generate their sound in free space forward and backward, rather than sending half toward you and half into a sealed enclosure or an enclosure with a hole in it. Because of their highly coherent, figure-eight wavelaunch, line sources like the Maggies tend to interact less destructively with listening rooms than quasi-point-source cone speakers do. They have little-to-no floor or ceiling bounce, zero output immediately to their sides, an out-of-phase backwave that is mostly dissipated by the room itself, close to uniform power response on- and off-axis, and zero cabinet diffraction. This doesn’t mean that they are a snap to set up; they are anything but. It just means that once properly positioned, they don’t add as much room sound to the presentation as typical dynamic speakers do. Combine this with their boxless openness, free-standing imaging, vast soundstage, phenomenal resolution of inner detail, lightning transient response, and neutral timbre, and Maggies seem markedly less ‘there’ as sources than almost any dynamic-speakers-in-a-box I’ve heard.

“Third, like electrostats Maggies use extremely lightweight membrane drivers that have a much larger radiating area than cone drivers do and that, unlike cone drivers, are uniformly driven over their entire surface, making for lower distortion and higher linearity in their passbands. Unlike cones, Maggies do not need extremely steep crossovers to keep breakup modes at bay (although, to be fair, Magnepan has in the past played various tricks to mask the differences in speed, distortion, and resolution among its planar-magnetic, quasi-ribbon, and true-ribbon drivers). Even though I have some quibbles about earlier iterations of large single-panel Maggies (for which see the next paragraph), at their best Magnepans are very nearly as fast on transients, as high in resolution, as low in coloration and distortion, and as truthful in timbre as the most discerning electrostats (and considerably deeper-reaching and more powerful and linear in the bottom and top octaves than many ’stats).

“Having said all this, let me admit that in my experience Maggies have also been among the most consistently frustrating loudspeakers I’ve heard and owned. When a component is nearly incomparable in certain respects, over time the areas in which it falls short (and all speakers fall short) start to weigh on you like Marley’s chains. And until recently, the Maggies, particularly the large single-panel Maggies (the 3.7s and the 20.7s), brought burdens as well as blessings.

“First, there was the matter of driver-to-driver coherence. While Magnepan’s true ribbon tweeter is a technological and sonic marvel, to my ear it never blended smoothly with Maggie’s quasi-ribbon drivers. (This is precisely why I’ve always preferred Maggie’s all-quasi-ribbon 1.7 series to the larger single-panel speakers in its line. Yes, you lost some of the extension, resolution, and sheer glamour of Maggie’s true ribbon on the top end—and you lost some of the amazing soundstage size and low-end reach of the bigger ’Pans—but what you gained back in octave-to-octave smoothness was well worth the sacrifice.)

“Second, line-source Maggies do not have the laser-cut image focus of quasi-point-source cones; their images are quite a bit larger than those of box speakers, which is something that takes getting used to (or not). With big ensembles or big instruments like pianos or drumkits, this isn’t a problem; in fact, it is quite realistic. But vocalists can sometimes seem slightly outsized—and flat in aspect.

“Which brings me to three: Maggies (or at least latter-day ones) don’t have quite the same three-dimensional body as cone speakers. And that is because they don’t have the power-range warmth and fullness (or box coloration, depending on your point of view) of cone speakers. To be fair, large single-panel Maggies have sometimes seemed a bit sucked-out in the power range (a byproduct, perhaps, of their dipole radiation pattern—and the bass-range phase-cancellation that can engender), and though quite extended and well defined in the bottom octaves they don’t do slam the way big dynamic speakers do. On acoustic instruments that play down into the low bass, such as doublebasses, timps, piano, organ, contrabassoon, they are nigh incomparably realistic. On Fender bass, synth, rock drumkit, or any instrument that is as much about power and impact as it is about pitch, timbre, and duration, the thrill, though not gone, is not there the way it is with, oh, top-line Wilsons.

“Fourth, big Maggies are, well, big and not particularly attractive loudspeakers that do anything but disappear in a listening room. Though I’ve heard them perform quite well in smaller spaces, they tend to like larger ones and, regardless of the size of the listening space, they thrive on power. Though not difficult to drive, they are low in sensitivity and need lots of amplifier, though they don’t necessarily need crème de la crème amplification.”

Since I wrote these words in 2018, a couple of new entries in the Maggie lineup have shaken things up. The first is the MG30.7, which, its enormous size notwithstanding, solved a goodly number of the sonic problems of larger Maggies. The second is the speaker I’m about to review.

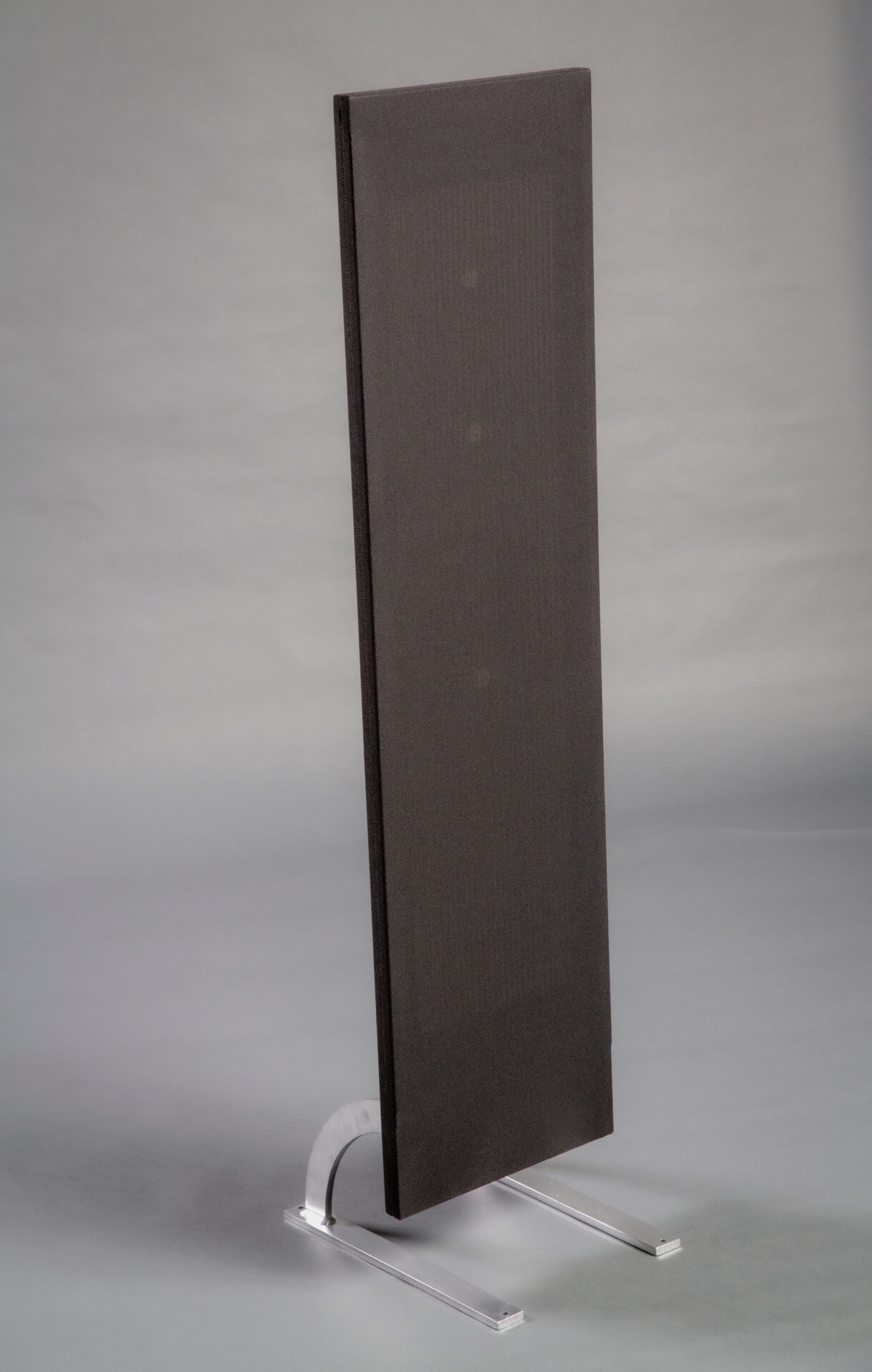

The $995 LRS+ (add another $289 for a pair of its optional and, IMO, essential steel stands) is a new and improved version of Maggie’s LRS (Little Ribbon Speaker)—a four-foot-tall, one-foot-wide, one-inch-thick “baby” Magnepan, expressly designed to fit into smaller, condo-like spaces. Previously, the littlest Maggies, such as the MMGs, used a mix of quasi-ribbon tweeter and planar-magnetic mid/woof panels. The LRS did not. Both the tweeter and the mid/woof sections of its diaphragm were quasi-ribbon, which is to say they used featherweight 0.001″-thick strips of aluminum foil, rather than much heavier wires, to transmit the signal to the 0.0005″-thick Mylar substrate to which they were bonded.

The advantages of quasi-ribbon technology are manifold. In addition to conferring a sizable reduction in mass, which allows diaphragms to start and stop more quickly and lowers “drumhead” resonances, the aluminum-strip voice coils of quasi-ribbons run the entire length of the panel, top to bottom, and are closely spaced across the panel’s breadth. As a result, the electrical signals they are fed, and thus the magnetic fields they generate, are distributed more fully and uniformly to the Mylar diaphragm beneath them, improving accuracy, resolution, bandwidth, and power handling.

The $750 all-quasi-ribbon LRS was a breakthrough—a genuine improvement in the fidelity of the smallest-footprint Magneplanar. What made it special is what makes all the best Magneplanars special: its midrange was uncannily realistic sounding. What made it less than fully rave worthy was, well, everything else. Its upper midrange was rough and brightish, its top treble was rolled off, and its low bass and power range were virtually non-existent. Of course, we’re talking about a small two-way planar loudspeaker. For $750, it would be beyond greedy to expect it to run the gamut. Where the LRS played it was mostly marvelous, only it didn’t play everywhere and had a few coherence issues in spots where it did.

Comes now a new version of the LRS, the LRS+, with a substantially higher price tag than the original ($538 higher if you include, as I think you must, its optional stands). Those greatly improved stands aside, the Plus doesn’t look any different than the original LRS. Its dimensions and weight are nearly the same (the LRS+ is an inch narrower). It is still a small, two-way, quasi-ribbon dipole. It is still sold in left/right pairs. Its printed specs are identical. Why would any budget-minded LRS owner want to consider junking or re-purposing what he’s already got to buy this new offering?

Well, it sounds better is why. And not just a little better. Indeed, Wendell Diller (who has done the design work on Magneplanars since Jim Winey retired) has successfully addressed the very issues that marred the original’s resume. That roll-off in the treble? Not vanquished, but ameliorated. That roughness in the upper mids? Smoothed out like a dress shirt fresh from the ironing board. Reduction of that nosedive in the power range and midbass? Done as if by order (to inappropriately quote Fred C. Dobbs).

What has changed in the design of the speaker to yield these improvements? You got me.

Here’s the problem with Magnepan. It is an Old School company and Wendell is an Old School guy. Despite incessant questions, he just won’t reveal what he (I think mistakenly) regards as state secrets. Where other outfits—Magico, for instance—are more than happy to show and tell you exactly what they’ve done to improve their transducers, Maggie and Wendell are not. Frankly, in today’s world this needs to change. Unless a new technology or device has a patent pending on it, there is no legitimate reason to play dumb. It only creates confusion, which isn’t good for anyone’s business.

Though I could make some guesses about what’s different in the Plus, they’d only be guesses. Maybe the crossover point and crossover parts have been changed, though, of course, it would still be a first-order slope, which is all that Maggie has ever used. Maybe panel tensioning and framing have been improved, and the ratio of membrane-space devoted to the lows and highs has been slightly altered. Maybe the Mylar used for the diaphragm has been reformulated or further thinned down. Ditto for the aluminum-foil voice-coil strips. The truth is I just don’t know.

The only change I’m sure of is the one to the height and mass of those optional stands, which are much sturdier and elevate the panels attached to them higher than Maggie’s traditional, ground-level, bent-metal feet (still supplied with the Plus). But the main sonic differences between Plus and Non-Plussed can’t be the result of their new shoes. Having had a good deal of experience with mass-loaded, after-market Magneplanar stands, I know their typical effects—and deeper bass and richer tone-color aren’t two of them. Yes, support systems can improve focus and resolution by lowering vibratory blur, but (typically) they also lean down timbre, particularly in the power range and midbass, which is the exact opposite of what I’m hearing from the Plusses.

It’s all rather frustrating for a reviewer and for a potential buyer. To market a speaker that looks almost exactly like the one you’ve already reviewed/bought but costs 66% more (with optional feet) and sounds a whole lot better without any explanation of what’s making for the improvements isn’t fair play. Unfortunately, that’s how it is. So, with the understanding that I’m unable to tell you what produces them, let’s talk about the sonic changes in the Plus.

Perhaps the first thing you will notice (I certainly did) is the difference in the low end. The LRS had none—or none below 90–100Hz or so. Which meant that what could you hear of lower-pitched instruments or instruments playing in their bottom octaves was almost completely “implied” by harmonics. The full power, color, and impact of things like double basses, bass drums, piano, organ, tuba, bass clarinet, bassoon, contrabassoon, trombone, cello, French horn, harp—virtually the entire underside of the orchestra—just weren’t there. It was like listening to music performed by wraiths, like those ghosts and skeletons that cavort to the player-piano version of “Danse macabre” in Renoir’s Rules of the Game.

When properly set up (for which, see below), the LRS+ offers a considerably more complete sonic picture. No, it won’t dip much lower than 60Hz (at least it won’t with authority and linearity), but in the 60Hz–200Hz range, the lower part of the power range, it is a much more robust, linear, detailed, and lifelike critter than the original. It gives you back a good deal of the foundation that the LRS robbed you of. It gives you back much of the power of the orchestra (to re-coin a phrase).

Now, let me be clear about this. No Maggie, certainly not its smallest offering, is going to sound like a Stenheim Alumine Five SE or an Estelon X Diamond II in the power range and low bass. It just isn’t going to deliver the color, dynamics, extension, body, and the ensuing chills and thrills of those great cones-in-a-box loudspeakers, particularly on electronically amplified (i.e., rock and blues) music. Oh, you’ll get some lifelike impact from the Plusses, for sure—enough to surprise and delight you, particularly if you’re used to listening to the original LRSes—and you’ll get fuller color and definition (along with superb transient detail) in the midbass on acoustic instruments like plucked or bowed bass. You just won’t get the whole gamut of that instrument below 60Hz or so, and you won’t get any of the near-subterranean reach of synth or five-string electric bass on great LPs like Brothers in Arms or Let’s Rock or Sinematic.

You could, of course, try subwoofing. But mating a Maggie, any Maggie, with a subwoofer is a very tricky proposition. Usually, in a Maggie-based system, the boxiness, floor bounce, and induced room resonances of a direct-radiating sub immediately call attention to it as a sound source, which is the exact opposite of what Magneplanars do on their own. In addition, no matter where and how steeply you cross them over, the “masking” effects that subs generate in the crossover region and above can rob Maggies (and dipoles in general) of enough transparency, tonal neutrality, and resolution to play havoc with the boxless purity of their un-woofed sound and invalidate the very reasons you bought them. On top of this, a sub adds complexity to an LRS+ system and eats up space. Why purchase an inch-wide “baby” planar in the first place if you’re gonna add hefty cones-in-boxes to the system?

The second thing you’ll notice (or maybe the first, depending on your listening taste) is the difference in the upper midrange and treble. What was rough and curtailed is now smoother, a bit more extended, and better blended with the rest of the spectrum. The difference is almost as profound as the difference on the bottom, and in some ways more important. After all, you can live with a speaker that has little-to-no bass and virtually no top treble—or what’s an LS3/5A for? It’s a lot harder to live with a speaker that is rough and irritating in the 1kHz-to-4kHz range, the area where the ear is most sensitive.

Now, I wouldn’t say the original LRS was shrill. It’s just that the complete absence of bass tends to turn a spotlight on nonlinearities in the upper mids and lower treble, making them stand out more than they would if they were counterbalanced by richer, more natural low-end/power-range timbre, body, and impact. As a result, there was a brightness and forwardness to the LRS’ presentation that did not, as I just said, verge into outright unpleasantness (or did not do so often) but was, nonetheless, audible. This upper-midrange roughness was made even more apparent by the LRS’ nosedive in the top treble, which (like the absence of bass) tended to isolate and spotlight the upper mids.

Robbed of a needed bit of treble extension and linearity, the LRS was altogether too lean and limited on top. The Plus is less so. As with its bottom octaves, the new LRS restores a measure of smoothness, sweetness, air, and life to the high end of the orchestra. You can hear this on virtually any recording of violin, viola, flute, clarinet, oboe, trumpet, English horn, harpsichord, or upper-octave piano. Add this newfound top and bottom smoothness and extension to what was already a fabulously lifelike midrange, and you get a loudspeaker that, on a great recording, can almost fool you into thinking you’re listening to the real deal.

Take for example, Ornette Coleman’s wonderfully idiosyncratic cover of the Gershwins’ “Embraceable You” from This Is Our Music [Atlantic/Wax Time]. Through the best box speakers this is a very natural sounding track, but even the best box speakers don’t do timbre the way Maggies do. It’s like the difference between hearing music in a good hall and hearing the same music played out of doors. Through the Maggies, a layer of box, driver, room coloration is lifted. As a result, the unique plasticky timbre of Coleman’s Grafton alto sax and the leaner, less robust color and power of Don Cherry’s pocket trumpet are reproduced with a neutrality and fidelity that most cones-in-a-box speakers don’t offer to quite the same degree. Through dynamic speakers, Coleman’s alto sounds just a bit more like a standard metal instrument; Cherry’s pocket trumpet a bit more like a full-sized one. Granted, this added richness and luster may be more appealing to many listeners (including me, sometimes), but the fact remains that it is less true to life.

The same is the case with vocalists. Of course, Maggies are famous for the naturalness with which they reproduce the human voice. (Some of the most lifelike reproduction of male and female singers I’ve experienced in better than 50 years of listening has been through various iterations of Magneplanars—Neil Diamond singing “Girl You’ll Be A Woman Soon” via Maggie 1Ds; Lou Reed singing “Walk on the Wild Side” via MGIIs; Dolly Parton, Emmylou Harris, and Linda Ronstadt singing various cuts from Trio via MG3.5s; Son House singing “Death Letter” via MG30.7s; countless other vocalists through MG1.6s and MG1.7s.) Because of their diminutive size and smaller panels, the Plusses will not only reproduce singers with Magneplanars’ characteristic in-the-room-with-you realism (try Ry Cooder and Taj Mahal on “Deep Sea Diver”—a bawdy tune that, as TAS’ Jeff Wilson wryly observed, isn’t likely to make it into the next Cousteau Society documentary); they will also do so with tighter image focus than taller, wider, larger-panel Maggies.

Before discussing the Plusses’ downside, I need to say a word about setup. In the old days, Maggies were typically listened to head-on, without any toe-in, for greatest neutrality. A lot of folks still prefer this alignment, but…it won’t work ideally with the LRS or the LRS+. Because of the smaller size of their quasi-ribbon panels and the fact they are two-ways, you may end up with either too much bass or too much treble and not enough in between—i.e., with too dark or too bright a tonal palette—if you don’t cant the speakers in a fair amount (at least 15–20 degrees). Though this may be room-dependent, Maggie also recommends that the speakers be situated with their tweeters (visible via a flashlight shined through the grille as the section of the panel with narrower, more closely aligned foil strips) to the outside and away from the wall and, with the requisite toe-in, their woofers to the inside and closer to the wall. My description of the sound of the LRS+ reflects Maggie’s set-up recommendations, albeit with toe-in painstakingly tweaked almost degree by degree until I achieved a balance that was neither too top-down or too bottom-up but audibly and measurably close to neutral.

Now for the downside. Let’s face it: Any planar (any speaker) that costs under a grand is going to have its limitations. Though they are considerably less severe than those of the original LRS, the Plus still has a few. I’ve already mentioned its restricted low bass. Though this may be ameliorated slightly by situating the speakers closer to the backwall (and taking advantage of a bit of room gain), the Plus is never going to go down with satisfactory linearity into the 40Hz–50Hz octave (and 30Hz and 20Hz you can forget about). Its improvement is more or less confined to the midbass (and up), which is a big step forward over the original but still nothing like what you’ll get (for 72 times the dough) from a Stenheim Alumine Five SE.

Again, its upper mids and lower treble are smoother and less roughed up than those of the LRS, but since the top treble is still a bit rolled, the Plusses can sound a little “exposed” on cymbal or flute or high-pitched violin, as if some of the air, lilt, and native harmonic sweetness and extension of the instruments have been squeezed down or out of the music. Nonetheless, this is still an area where the Plus is substantially improved over the LRS.

Like all Magneplanars, but more so, the LRS+ has dynamic constraints. The excursion limits of Maggie’s panels are considerably greater than those of the best cone drivers. On top of which, the smaller panels of the Plus mean less air is being moved to begin with. Though I haven’t been able to make them clip, even at very loud levels, these baby Maggies aren’t going to maintain 100+dB average SPLs (or 105+dB peaks) without complaint. Also, with a sensitivity of about 83dB they are going to need plenty of power.

An additional limitation associated with the speaker’s diminutive size is soundstage dimensions. This is not as much of a problem when it comes to depth and width, but it does show up early and often when it comes to image height. Sonically, this is a mix of good and bad. As I already said, on voices you don’t get the typical Maggie “bigness,” which will be a positive thing for many listeners. Singers are less outsized and better focused through the LRS+. On the other hand, so are certain naturally large instruments, such as pianos and drumkits. In a speaker of these dimensions, you can only expect that so many attributes of acoustic instruments will be reproduced with complete realism—and the sheer volume of a nine-foot concert grand isn’t one of them.

Bottom line: The LRS+ is a big improvement over the original LRS. It adds enough color, power, detail, and extension in the midbass and smoothness and coherence in the upper mids and lower treble to make it far more of a true full-range contender than its predecessor. Though you can do better in the Maggie line for about three times the money (the MG1.7i), you’re not going to get the same condo-friendly form factor from the 1.7, which is a foot and a half taller and a half foot wider than the Plus. In cone speakers, you can find much smaller boxes at this price point and, for a bit more money, some self-powered models, but not a one of them that I’ve heard comes as close to sounding like the real thing as this baby Maggie. For folks who are new to the high end or have small listening spaces or are working with limited budgets or just want a second high-fidelity system in a different spot for music or TV, I can think of no better choice for the dollar, particularly if you treasure the sound of acoustic instruments. Its limitations notwithstanding, this is a great little loudspeaker and a sure-fire nominee for one of TAS’ 2022 Product of the Year Awards.

Specs & Pricing

Type: Two-way, quasi-ribbon, dipole, floorstanding loudspeaker

Frequency response: 50Hz to 22kHz

Sensitivity: 83dB/2.83V/500Hz @1 meter

Impedance: 4 ohms

Dimensions: 13½” x 48″ x 1¼”

Shipping Weight: 40 lbs./pair

Price: $995 (optional stands, $289)

MAGNEPAN INCORPORATED

1645 Ninth Street

White Bear Lake, MN 55110

(800) 474-1646

magnepan.com

JV’s Reference System

Loudspeakers: MBL 101 X-treme, Stenheim Alumine Five SE, Estelon X Diamond Mk II, Magico M3, Voxativ 9.87, Avantgarde Zero 1, Magnepan LRS+, 1.7, and 30.7

Subwoofers: JL Audio Gotham (pair)

Linestage preamps: Soulution 725, MBL 6010 D, Constellation Audio Altair II, Siltech SAGA System C1, Air Tight ATE-2001 Reference, Zanden 3100

Phonostage preamps: Soulution 755, Constellation Audio Perseus, DS Audio Grand Master

Power amplifiers: Soulution 711, MBL 9008 A, Aavik P-580, Constellation Audio Hercules II Stereo, Air Tight 3211, Air Tight ATM-2001, Zanden Audio Systems Model 9600, Siltech SAGA System V1/P1, Odyssey Audio Stratos, Voxativ Integrated 805

Analog source: Clearaudio Master Innovation, Acoustic Signature Invictus Jr./T-9000, Walker Audio Proscenium Black Diamond Mk V, TW Acustic Black Knight/TW Raven 10.5, AMG Viella 12

Tape deck: Metaxas & Sins Tourbillon T-RX, United Home Audio Ultima5 OPS

Phono cartridges: DS Audio Grandmaster, DS Audio Master1, DS Audio DS-003 Clearaudio Goldfinger Statement, Air Tight Opus 1, Ortofon MC Anna, Ortofon MC A90

Digital source: MSB Reference DAC, Soulution 760, Berkeley Alpha DAC 2

Cable and interconnect: CrystalConnect Art Series Da Vinci, Crystal Cable Ultimate Dream, Synergistic Research SRX, Ansuz Acoustics Diamond

Power cords: CrystalConnect Art Series Da Vinci, Crystal Cable Ultimate Dream, Synergistic Research SRX, Ansuz Acoustics Diamond

Power conditioner: AudioQuest Niagara 5000 (two), Synergistic Research Galileo UEF, Ansuz Acoustics DTC, Technical Brain

Support systems: Critical Mass Systems MAXXUM and QXK equipment racks and amp stands and CenterStage2M footers

Room Treatments: Stein Music H2 Harmonizer system, Synergistic Research UEF Acoustic Panels/Atmosphere XL4/UEF Acoustic Dot system, Synergistic Research ART system, Shakti Hallographs (6), Zanden Acoustic panels, A/V Room Services Metu acoustic panels and traps, ASC Tube Traps

Accessories: DS Audio ION-001, SteinMusic Pi Carbon Signature record mat, Symposium Isis and Ultra equipment platforms, Symposium Rollerblocks and Fat Padz, Walker Prologue Reference equipment and amp stands, Walker Valid Points and Resonance Control discs, Clearaudio Double Matrix Professional Sonic record cleaner, Synergistic Research RED Quantum fuses, HiFi-Tuning silver/gold fuses

Tags: FLOORSTANDING LOUDSPEAKER MAGNEPAN

By Jonathan Valin

I’ve been a creative writer for most of life. Throughout the 80s and 90s, I wrote eleven novels and many stories—some of which were nominated for (and won) prizes, one of which was made into a not-very-good movie by Paramount, and all of which are still available hardbound and via download on Amazon. At the same time I taught creative writing at a couple of universities and worked brief stints in Hollywood. It looked as if teaching and writing more novels, stories, reviews, and scripts was going to be my life. Then HP called me up out of the blue, and everything changed. I’ve told this story several times, but it’s worth repeating because the second half of my life hinged on it. I’d been an audiophile since I was in my mid-teens, and did all the things a young audiophile did back then, buying what I could afford (mainly on the used market), hanging with audiophile friends almost exclusively, and poring over J. Gordon Holt’s Stereophile and Harry Pearson’s Absolute Sound. Come the early 90s, I took a year and a half off from writing my next novel and, music lover that I was, researched and wrote a book (now out of print) about my favorite classical records on the RCA label. Somehow Harry found out about that book (The RCA Bible), got my phone number (which was unlisted, so to this day I don’t know how he unearthed it), and called. Since I’d been reading him since I was a kid, I was shocked. “I feel like I’m talking to God,” I told him. “No,” said he, in that deep rumbling voice of his, “God is talking to you.” I laughed, of course. But in a way it worked out to be true, since from almost that moment forward I’ve devoted my life to writing about audio and music—first for Harry at TAS, then for Fi (the magazine I founded alongside Wayne Garcia), and in the new millennium at TAS again, when HP hired me back after Fi folded. It’s been an odd and, for the most part, serendipitous career, in which things have simply come my way, like Harry’s phone call, without me planning for them. For better and worse I’ve just gone with them on instinct and my talent to spin words, which is as close to being musical as I come.

More articles from this editorRead Next From Review

See all

Oswalds Mill Audio K3 Turntable

- Apr 12, 2024

2023 Golden Ear: Schiit Freya S Preamplifier

- Apr 12, 2024