It is with great sadness that we announce the passing of Harry Pearson, Founder of The Absolute Sound and an icon of high-end audio journalism. Harry passed away at his home in Sea Cliff, New York at the age of 77. The staff of the magazine Harry created more than 40 years ago will post their tributes to the man and his great legacy over the coming days. We’ll begin our remembrances with this piece by Jonathan Valin, published in the July/August, 2013 issue on the occasion of The Absolute Sound’s 40th anniversary.

TAS At 40

Some Thoughts on our Fortieth Anniversary

Jonathan Valin

When Harry Pearson founded The Absolute Sound forty years ago, in the spring of 1973, the magazine was digest-sized and staple-bound; there were no advertisements (manufacturer or dealer) in its pages; the Reference System was the consensus choice of editor and senior contributors; the first reviews were commented upon by other reviewers (chiefly JWC and PHD); and the coverage of “certain divisions of modern music” (read “rock ’n’ roll”) was not in the design brief. The goal was to discover and extol those products that came closest to reproducing the absolute sound—the sound of (primarily classical) music as heard in a concert hall. The enemy was relativism—the leveling of judgment and the differences upon which judgments were reached by the mainstream hi-fi magazines (Stereo Review, Audio, and High Fidelity), which proclaimed all products more or less sonically equal, in part because it was in their financial interest to do so in order to avoid offending advertisers, and in part because the measurements and numbers the “slicks” depended on to form these judgments tended (on paper or in theory, at least) to make all products of the same type look more or less alike. Though scientific measurement was not ruled out by HP, it was the ear, an “infinitely more subtle and sophisticated measuring device than the entire battery of modern test equipment,” that was to be the final arbiter.

The ear and the mind, of course.

From go, The Absolute Sound was unusually thoughtful about what came to be called “the high end.” As HP pointed out in that first editorial, the magazine’s very mandate required the philosophical assumption that there is an absolute in the reproduction of music—a referential reality to which the recorded thing can and should be fruitfully compared. Such idealism (for that is what it was and is) went strongly against the pragmatic tide of then-current audio criticism. Even Stereophile, J. Gordon’s Holt’s pioneering “subjectivist” hi-fi magazine, made more room for different kinds of listeners than HP did. (Remember JGH’s shorthand descriptions of recommended products—those long strings of individual letters that symbolized what might be called “‘stereo’-types,” recurrent groups of sonic qualities that often seemed to be found together and that he associated with listeners with different sonic tastes?) For The Absolute Sound as it was originally conceived there was only one type of listener—the classical music lover, with long concert-hall experience, seeking the most convincing illusion of the sound of acoustic instruments in a real space. Although philosophical room was made for disagreements or differences of opinion about how close a given component came to the sound absolute, the primacy of “the absolute” was fundamental.

For all its refreshing candor and the salubrious effect it had (and the occasional injustices it visited) on designers, manufacturers, and listeners, there always was and still is a bit of a conundrum built into HP’s idealistic standard—to wit, the question of whether “the absolute sound” is in fact an absolute (as opposed to a relative) thing, whether “the sound of real instruments in a real space” remains the same regardless of who is doing the listening, where that listener is seated, what effects the hall/studio has had on sonics, and what kind of music and instruments are being played.

Harry used to address this conundrum by pointing out that you could always tell the real thing from the recorded one when in the presence of each—could always tell that an actual marching band passing by your open window sounded different than a recorded marching band on your stereo, and that the fundamental difference in kind between the real thing and the reproduced one was unmistakable no matter the listener, the vantage, the hall, or the music/ensemble. It is this, Pearson’s somewhat broader view of the absolute sound—which emphasizes the perceived differences (and similarities) between the real thing and the recorded one—that has inspired a good deal of the current writing in The Absolute Sound and inspired me, personally.

I suppose this is another way of saying that much has changed since that first issue of TAS. Indeed, the change started with the first issue of TAS.

When Harry launched the magazine the sun had set on the Golden Age of Hi-Fi. In the U.S. the audio industry was in limbo, trying to find its bearings in the new age of the transistor and in the face of ferocious overseas competition. Whether it was good fortune or editorial good taste or a little of each, TAS’s founding coincided with a sea change in the market. Small companies founded by brilliant iconoclastic engineers as attuned to sonic realism and as uncompromising as Harry himself—companies that might’ve gone unnoticed or underappreciated were it not for HP, John Cooledge, Patrick Donleycott, and the other TAS pioneers—began to proliferate. Almost all of them eventually found a home in the pages of The Absolute Sound.

One only has to look at the reviews in the first four issues (from Spring 1973 to Spring 1974) to appreciate the rapidity and drama of this change. In addition to the famous review of The Double Advent System (which made Harry’s and The Absolute Sound’s reputation, in spite of the fact that the Original Advent loudspeaker had been around since the mid-1960s), you find commentary on other fairly-well-known “older” components like the ADC XLM and the Citation 11 and the Phase Linear 700. (The reason for this look backwards was because it was TAS’s collective editorial opinion that none of these products had received their just due in the everything-sounds-more-or-less-alike mainstream press.) However, in Issue One you also find a forward-looking review (by JWC) of a newcomer, the Dayton-Wright XG-8 electrostat—a tip-off to what was to come. While there is still plenty of older, better-established stuff in Issue Two, there is also Harry’s groundbreaking review of the Magneplanar I-U/I-D, the planar-magnetic speaker system that, despite any flaws (and HP pointed out a few), upped the ante on realism in full-range transducers. By Issue Three we get the Audio Research Corporation SP-3. By Issue Four (the one with the Vikuspic drawing of Harry wearing headphones for sunglasses on the cover) the Dahlquist loudspeaker, the ARC SP-3a preamp, the FMI 80 stand-mount/bookshelf, the Marantz 500 amp (woe and alas), the Dynaco 400 amp, the ARC Dual 76 amp, the Dayton-Wright XG-8 Mk II, the Supex moving-coil cartridge. And after that…well, a continuous parade of exciting new products mixed with worthy older ones.

With a few long-lived exceptions like Quad, KEF, Ortofon, and McIntosh, most of the marques that we consider old standbys today were newcomers then—so many of them in such rapid succession, from so many talented individuals around the country and the world, that this revolution in hi-fi acquired a new name, the “high end,” to distinguish its sonic aspirations, listener appeal, and, yes, often (but not always) higher price tags from the mass-market goods of mid-fi. While it would be an overstatement to say that TAS created high-end audio, it certainly helped usher it in—weeding out the pretenders from the keepers by comparing both to the ideal of the absolute sound, creating a market of its own readership for products that excelled in this comparative test, and making audio seem exciting again by injecting wit, no-nonsense judgment, and a clubby sense of exclusivity—of those-in-the-know and those-not—into the once-technocratic world of audiophilia. Pearson and company made audio gear more exciting by talking about it in plain English rather than via circuit diagrams or mathematical formulae, by creating a vocabulary (as did Gordon Holt) and a standard of comparison that “ordinary” music lovers could relate to and make use of, and by calling a spade a spade when it came to good, better, and best.

Who didn’t look forward to the next Absolute Sound? Who didn’t read it avidly, practically memorizing each turn of phrase? Who didn’t salivate over the stuff that made the cut—or run out and buy the records on HP’s famous Recommended List (for part of HP’s philosophy was that LPs must pass the same absolute-sound test as hardware—that recordings must be worthy of the equipment they are played back on).

For almost two decades, TAS flourished, “setting the market” for high-end cognoscenti in both hardware and software. Then, as the revamped (by John Atkinson and Larry Archibald) Stereophile began to nip at its heels and ultimately overtake it in revenue and readership, TAS fell on hard times.

Personally, I think there were several reasons for TAS’s decline in the early-90s. First, as noted, the competition became stiffer. Second, the business of running the magazine, both financially and editorially, was sometimes willfully mishandled. Third, there was a reaction to the (let’s face it, deliberately cultivated) “guru” mentality of the past two decades—to the idea of a single man or school of thought (and all TAS writers at that time, including me, were versions of HP, by fiat using his lingo, paying due respect to his past and present judgments, trying to think the way he thought) determining what was good and what was bad by the sole standard of how well a component conformed to the sound of acoustic (chiefly large-scale classical) music. Which brings us to four—the decline of classical music and the ascent of rock, not just among the broader public but more critically among audiophile readers of The Absolute Sound, who, after all, grew up with the stuff. This shift in (or expansion of) musical taste had been going on for decades, of course. But (then-TAS-contributor Michael Fremer excepted) you wouldn’t have known it from most of the pages in TAS. The trouble was that the canonic absolute sound test simply didn’t work with electronic rock ’n’ roll (unless you considered vocals only—and even then there were complications). HP’s broader test—the perceived realism of the reproduction—did, but it wasn’t applied until well after the bottom fell out in the later 90s and TAS temporarily went under.

Then a miracle happened. A TAS subscriber from Issue 1 and a longtime HP fan named Thomas Martin bought the magazine in 1998 and, about three years later, installed Robert Harley as Editor in Chief. The current commercial success of the magazine—and it has never, in all its history, been more successful or influential—dates precisely from this change in leadership and the consequent change in editorial style and content that it brought about.

Though HP continued (until recently) to be a valued contributor with his own section of the magazine —HP’s Workshop—the rest of the writing staff was let “off the leash.” TAS writers were encouraged to use their own words, to do their own thinking about what they were writing about (and refer to their own music), to hew to the absolute sound philosophy but to interpret it after their own fashion. The results were a broader spectrum of opinion and judgment—no less candid or seasoned by experience but more varied and less dogmatic—a more conversational and far less snobbish tone, more professional relationships with manufacturers (who now got reviewed in a timely fashion rather than having to wait, often fruitlessly, for months and years to see commentary in print) and with readers (who were no longer subjected to an endless stream of lazy “non-review” reviews, in which nothing but the vaguest—and often grossly inaccurate—descriptions were offered and the vaguest conclusions were reached, though more was constantly being promised, and seldom delivered), more professional editing and fact-checking, and a wider scope of product coverage.

This change in tone, style, and overall professionalism had no effect on the magazine’s pioneering spirit—its “ahead of the curve” approach to the best in high-end audio. Since Robert took over, TAS has been the first (and most reliable) in print on major new players like Magico, Soulution, TAD, Constellation, Raidho, Carver LLC, Hegel, Estelon, BAlabo, Lansche, Venture, and YG Acoustics (among scores of others), kept faith with already well-established worthies like Magnepan, Wilson, ARC, c-j, NAD, AVA, PrimaLuna, Focal, MartinLogan, B&W, Lamm, KEF, Sonus faber, Nola, Vandersteen, PSB, Quad, Spectral, Sony, Simaudio, Bryston, Plinius, MBL, and many many more, been first to take critical looks at the latest high-end trends such as Class D amplification and USB audio, and regularly covered both affordable and cutting-edge gear in depth. Our appeal to readers has never been broader; our influence has never been more profound.

Yes, the “new TAS” is different than the old one. But the “plain speaking”—the candid, non-technical, “user-friendly” audio writing that Harry pioneered and the high standards of critical excellence—has not. The search for the absolute sound is still our quest, but it has broadened to include more musics and more listeners, other voices and other rooms.

For those readers who occasionally feel nostalgic for the good old days when HP ruled the roost and we were young (and, in certain moods, I can’t help but count myself one of them), let me quote HP himself on the way thinking about and judging high-fidelity gear really works (the absolute sound notwithstanding). I take this passage from his landmark editorial in the very first issue of TAS: “We will, among ourselves, disagree from time to time…. Such disagreements are likely when you consider the fact that all components are imperfect and that the real subjective choice in assembling good high-fidelity systems comes with the choice of which imperfections you can bear over the long run.”

That, folks, is the candid, commonsensical way of looking at the choices we perforce make about our mutual hobby and mutual passion. But then candor and commonsense (coupled with idealism) were what HP brought to the table starting with Issue 1—and what we at TAS pledge to continue in Issue 234 and beyond.

So happy fortieth birthday to TAS and all of you out there who’ve been with us on this long, sometimes bumpy, always interesting ride toward the never-to-be-fully-realized ideal of recreating the sound of music (all music) as it is heard in life, with its craftsmanship and powers of thought and feeling fully intact.

By TAS Staff

More articles from this editorRead Next From News

See all

The New Sonore opticalRendu Deluxe Has Arrived

- Apr 17, 2024

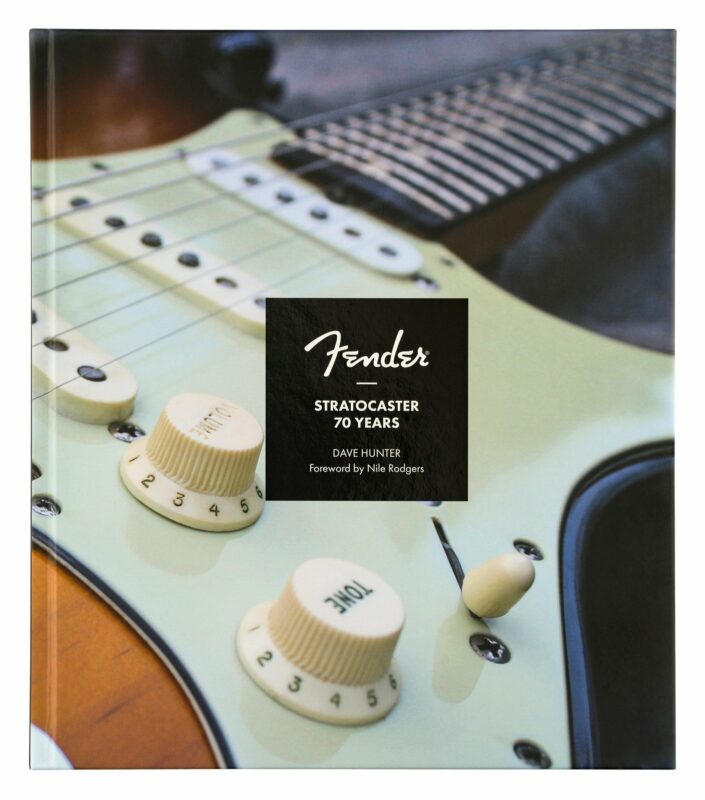

FENDER STRATOCASTER® 70TH ANNIVERSARY BOOK

- Apr 15, 2024

PowerZone by GRYPHON DEBUTS AT AXPONA

- Apr 13, 2024