Lamm Industries LP2 Deluxe Phonostage and Clearaudio Titanium Cartridge

- NEWS

- by Jonathan Valin

- Dec 15, 2008

I’ve been patting MBL speakers and electronics on the back so often lately for their transparency and resolution that the front-end components I’m about to review have been kind of lost in the shuffle. True, the “grip” of the 101 E Radialstrahlers, 6010 D linestage preamp, and 9011 monoblock amps on very low-level musical details is phenomenal; in combination, they simply don’t let go of a sound until the instrument stops sounding, reaching with greater clarity higher into fortissimos and lower into pianissimos than other electronics, and reproducing the way a note dies off so clearly and completely that you can hear the exact moment when the faintest sound stops and silence starts.

As I mentioned in my review of the ARC Reference 3 preamp and 210 amps in Issue 159, my locus classicus for this sort of thing is the first movement cadenza of the Montsalvatge Concerto Breve [London], where pianist Alicia de Larrocha sustains a note via finger and pedal for what seems like an eternity, providing a primer on the way a piano’s overtones gradually die out. With the MBL gear, the instant that de Larrocha finally lets up on pedal and key and that last little enharmonic overtone, which has been sounding at an extremely low level for several seconds, finally stops is so marked that the moment of rest which follows takes your breath away.

The clear divide between very-lowlevel sounds and silence is something you hear in concert halls all the time, but typically don’t hear on stereo systems, which tend to add enough of their own noise to obscure both. With this recording and the superb ARC tube gear, for example, you would be harder put to tell precisely when that last overtone stops and silence begins. The one just seems to vaguely meld into the other without an unambiguous line of demarcation. With the MBL electronics, the moment that overtone dies out is like a bank vault door closing.

On the other hand, in the instants between successive notes, the ARC gear has a magical ability to “hang” harmonics almost visibly in the air, so you can hear the way the colors of one note of, say, John Ogden’s Steinway—at the start of the great Andante of Shostakovich’s Second Piano Concerto— harmonize with and reinforce the colors of the next note, as you would (to an even greater degree) in life.

All of this perceived detail is a testament to the class-leading resolution of MBL and ARC electronics (and MBL’s second-line preamp, the $8000 5011, and second-line amp, the $40k 9008 monoblocks, belong in this same exalted company). But it is also a testament to the transparency of the Lamm LP2 phonostage, the Clearaudio Titanium cartridge, and the Walker Proscenium Gold record player that feed these preamps and amps.

This front end is a veritable pane of glass when it comes to low-level detail—and frankly to just about every other aspect of high-fidelity reproduction. It is also neutral enough to allow the ARC gear to show its set of virtues to full advantage and the MBL its rather different one, without stamping its own personality too markedly on either. Though other cartridge/phonostage/ record-player combos have significantly different virtues and several items on the horizon look promising, as a music source nothing I’ve yet heard betters the Clearaudio/Lamm/Walker, analog or digital. There was a time when I wouldn’t have said this—when I would’ve conceded that digital (particularly SACD) had the edge in reproducing certain kinds of details, particularly transient-related ones. And while I still think that CD/SACD is superior to the best analog in definition, extension, and impact in the low bass, everywhere else the Lamm/Clearaudio/Walker stomps it.

Since it was the addition of the $6000 Clearaudio Titanium cartridge that elevated the Lamm and Walker to new levels of clarity, I’ll start with it. The Suchys of Clearaudio (Peter, Robert, and Patrick) and their U.S. importer, Garth Leerer of Musical Surroundings, have been kind of vague about what it is that makes this movingcoil cartridge (one of several new “HD” Series Clearaudio moving coils, including the Gold, the Stradivari, and the Concerto) sound so much better. One difference is obvious. A flanged plastic disc—looking rather like a small gear or gigantic, serrated Marigo Dot—sits atop the cartridge where it mounts to the headshell. Playfully designated “magic fingers” by Leerer, it is said to serve some sort of decoupling/resonancecontrol function. Like most quasi-magical audio “tweaks,” the science of it is less important than the effect, which appears to be profound. Clearaudio cartridges have always been high in detail; this one is the highest yet, with simply unparalleled (in my experience) resolution of both attacks and decays from the midbass to the upper treble and a (to my ear) nearer-to-ideal tonal palette than Clearaudio has before achieved.

It has become a reviewer cliché to rhapsodize about how much more information remains to be discovered in the thirty, forty, and fifty-year-old grooves of old-standby LPs, but, folks, it is simply mind-boggling to play back a record you’ve heard scores of times—like the Rózsa Violin Concerto [RCA]—and hear new details in Heifetz’s bowing and fingering, and, best of all, in the sumptuous tone of his Guarnerius. Listening to this disc through MBL, ARC, and Edge electronics, I got the eerie feeling I was hearing a slightly different pressing of the LP with each pair of preamps and amps—fresh features were brought to the foreground by each combo. In combination with that of the Lamm LP2 Deluxe, the cartridge’s transparency to the source seems to make every disc a veritable smorgasbord of audio delights—a table so large and varied that no one set of electronics can sample all that is being offered.

The Titanium (so-called because it is housed in a titanium body) uses lowermass coils and higher-efficiency magnets than previous top-end Suchy designs, although both coils and magnets are configured in same “symmetrical” fashion as classic Clearaudios, and output remains a relatively high 0.8mV. The Titanium does have a completely new stylus, however— a design that the Suchys call “Micro HD.” I don’t know what geometric changes the Micro HD may entail,

The Titanium (so-called because it is housed in a titanium body) uses lowermass coils and higher-efficiency magnets than previous top-end Suchy designs, although both coils and magnets are configured in same “symmetrical” fashion as classic Clearaudios, and output remains a relatively high 0.8mV. The Titanium does have a completely new stylus, however— a design that the Suchys call “Micro HD.” I don’t know what geometric changes the Micro HD may entail,

but the resolution, tone color, transients, soundstaging, and transparency of the cartridge are doubtlessly attributable in part to the extremely low mass (0.00016 grams) of the HD stylus and perhaps to the high mass (9 grams) of the titanium housing, which is said to lower resonance and reflections and permit better dynamics. (Clearaudio claims a dynamic range of +95dB, which would explain the Titanium’s way with starting and stopping transients.) At a VTF of about 2.35 grams, the Titanium also tracks beautifully.

The Titanium isn’t perfect. It is not as thunderous or extended in the very deep bass as, say, the MBL 1621A/ 1611E CD player are. Though it has plenty of “oomph” on doublebasses, timps, piano, or low brass and winds, it won’t reproduce something like a battery of Tsuridaiko and Kakko drums or the synths on David Bowie’s Earthling [Sony] with the jaw-dropping impact of the MBL digital gear. On the tip-top it is just a little less stingingly dynamic than CD/SACD on attacks like cymbal strikes, although it compensates for this with greater treble-range air, superior extension, more natural tone colors, and simply marvelous decays. The way the

Titanium/Lamm hangs on to something like the long reverberation of the tamtam in the Decca recording of Henze’s charming ballet-cum-flute-concerto The Emperor’s Nightingale [L’Oiseau-Lyre] is something to marvel at. Its midband is, as noted, much more gemütlich than previous Clearaudio I’ve auditioned, though not overly warm after the fashion of a Koetsu or gravy-rich-and-thick like a Shelter. On a superb cut like “All My Trials” from Peter Paul & Mary’s In the Wind [Warner]—a record that really ought to be reissued by someone—it comes as close to making voices and guitars sound in-the-room-with-you there as anything I’ve heard from any source.

If the Titanium has added new layers of musical detail to my front-end setup, the $6990 Lamm Industries LP2 Deluxe phonostage has preserved them intact. To be honest it has taken me a very long time to appreciate the virtues of the LP2 Deluxe. When I first got it—several years ago, now—I thought it was too polite, too lacking in bloom, too dark and lifeless. Why, then, did I use it? Because it was also, and in spite of these serious deficiencies, dead quiet.

Vladimir Lamm lives and works in Brooklyn, where RFI is a genuine problem. Unlike certain other designers of phonostages, who seemingly live on mountaintops far from urban broadcast towers and who simply don’t appreciate how irritating it is to listen to an LP while a radio program intermittently drones on in the background, Vladimir feels your pain. Thanks to what is unquestionably the best step-up transformer around (the unit is made by Jensen Transformers) and elaborate RFI filtering of the AC voltage, he has seen to it that I don’t have to “tune out” some evangelist praising the Lord over the airwaves while Messaien praises Him after his own fashion on the turntable. Generally step-up devices rob you of transparency, and they do this at the very first link in the Great Chain of Reproduction, which means there is no way of compensating for what’s been lost. I don’t know what’s different about the Jensen transformer, but it is phenomenally transparent, and, since it isolates the signal from RFI/EMI contamination, phenomenally quiet.

The step-up transformer aside, you wouldn’t think that the LP2 would be a world-beatingly low-noise component, as it is all-tube save for one solid-state regulator for the heater supply. Vladimir, who likes to do things differently, makes a superb solid-state linestage preamp, the L2 Reference; for reasons only he can explain, he turned to Western Electric 417A/5842 triodes for his phono preamp. You might think this would soften the sound and grunge it up a bit, but it doesn’t. Indeed, you’d be hard put to distinguish the LP2 from its transistorized partner—it sounds so little like tubes. As noted, right out of the box it doesn’t sound particularly distinguished, either.

A friend and former employer of mine, Jerry Gladstein, once told me that the keys to getting the most out of the LP2 were time and patience. He was right. It takes a good six months of constant play to start to get the LP2 to straighten up and walk right. Even then it still sounds the slightest bit dark, overly controlled, and lacking in bloom compared to something like the Aesthetix Io. But even before it fully loosens up, its clarity will impress you, and when it finally does break in…folks, you ain’t heard nothing yet until you’ve heard this preamp with a truly high-resolution cartridge like the Titanium. It passes everything through, uncolored and unedited (save for that slight persistent darkness and reduction in bloom), making for what may be the most transparent source component I’ve yet heard.

With the LP2, what you get from the cartridge is essentially what you get from the Lamm unit’s outputs, which is why very different preamp/amp combos like the MBL 6010/9011 or 5010/9008 or the ARC Reference 3/210 or the Edge 1.1/12.5 not only sound markedly different but bring entirely different details of the recording to life. The LP2 just transmits the information, letting the preamps and amps pick and choose the emphases.

As different-sounding as they are, the presentations of all these preamp/amp combos do have certain things in common that are attributable to the LP2.

First, as noted, low-level transient and harmonic details are exceptionally clear, making attacks and decays more lifelike and producing the best reproduction of the duration of notes I’ve yet heard. With the right recordings, such as Viktor Kalabis’ Sonata for Violin and Piano [Panton], you not only get the whole note you get the whole mechanism by which that note was sounded. The LP2 (with the Titanium and Walker) positively illuminates the action of pianist Milian Langer’s piano, so that you can “hear” the depression of the keys, the felts of the hammers, the movements of the balanciers and the jacks. These are the kinds of detail that, as Robert Harley noted in our last issue, contribute to the “realistic” presence of an instrument and instrumentalist, and the LP2 gives them to you, to quote Sallie Reynolds, in spades and diamonds.

Second, bass is unusually welldefined and extended. As noted, the LP2 won’t give you CD definition and thwack on Japanese drums or bass synth, but as phonostages go it comes mighty close and is simply superb on low-pitched acoustic instruments, reaching deeper into the bottom than the Aesthetix Io but without all of the Aesthetix’s magical mid-and-upper-bass bloom.

Third, though the LP2 is a supremely transparent device, it is slightly sweet and forgiving—nothing ever really sounds awful through it, although whether this is a demerit I leave up to you. As for its tonal balance…at one early point in its sojourn, I thought the LP2 was darker than it actually is; either it or I have outgrown that phase, for it now sounds closer to neutral.

Fourth, because the LP2 lacks the helium bloom of something like the Aesthetix Io, instruments can sound slightly “flatter” through it than they do through classic tube phonostages. However, dimensionality depends to a large extent on what you feed the LP2 into. With linestages that are capable of 3-D imaging, such as the Edge or ARC Reference 3, you get a very satisfyingly three-dimensional sound.

Fifth, the LP2 is not a one-size-fits-all soundstager like the Zanden phonostage. As with bloom, it doesn’t over-inflate the stage, but passes on what’s on the record, letting the linestage/amp make its own interpretation of the data. If the linestage and amp are consistently big-sounding, like the Ref 3/210, the stage is enormous. If they are more size-neutral, like the MBL 6010/9011 or 5011/9008, then the stage grows and shrinks with the source. With speakers that are as capable as the 101 Es, and electronics that are as high in resolution as the MBL amps and preamps and the ARC amp and preamp, it is easy to forget how crucial the front end is. But its transparency to the source is, in fact, the key to all that follows, and in the case of the Titanium cartridge, the Lamm LP2 Deluxe phonostage, and the Walker ’table and arm, this transparency is so high that I seldom find myself listening to CDs or SACDs anymore. I can think of no higher compliment to pay an analog front end than that. &

By Jonathan Valin

I’ve been a creative writer for most of life. Throughout the 80s and 90s, I wrote eleven novels and many stories—some of which were nominated for (and won) prizes, one of which was made into a not-very-good movie by Paramount, and all of which are still available hardbound and via download on Amazon. At the same time I taught creative writing at a couple of universities and worked brief stints in Hollywood. It looked as if teaching and writing more novels, stories, reviews, and scripts was going to be my life. Then HP called me up out of the blue, and everything changed. I’ve told this story several times, but it’s worth repeating because the second half of my life hinged on it. I’d been an audiophile since I was in my mid-teens, and did all the things a young audiophile did back then, buying what I could afford (mainly on the used market), hanging with audiophile friends almost exclusively, and poring over J. Gordon Holt’s Stereophile and Harry Pearson’s Absolute Sound. Come the early 90s, I took a year and a half off from writing my next novel and, music lover that I was, researched and wrote a book (now out of print) about my favorite classical records on the RCA label. Somehow Harry found out about that book (The RCA Bible), got my phone number (which was unlisted, so to this day I don’t know how he unearthed it), and called. Since I’d been reading him since I was a kid, I was shocked. “I feel like I’m talking to God,” I told him. “No,” said he, in that deep rumbling voice of his, “God is talking to you.” I laughed, of course. But in a way it worked out to be true, since from almost that moment forward I’ve devoted my life to writing about audio and music—first for Harry at TAS, then for Fi (the magazine I founded alongside Wayne Garcia), and in the new millennium at TAS again, when HP hired me back after Fi folded. It’s been an odd and, for the most part, serendipitous career, in which things have simply come my way, like Harry’s phone call, without me planning for them. For better and worse I’ve just gone with them on instinct and my talent to spin words, which is as close to being musical as I come.

More articles from this editorRead Next From News

See all

The New Sonore opticalRendu Deluxe Has Arrived

- Apr 17, 2024

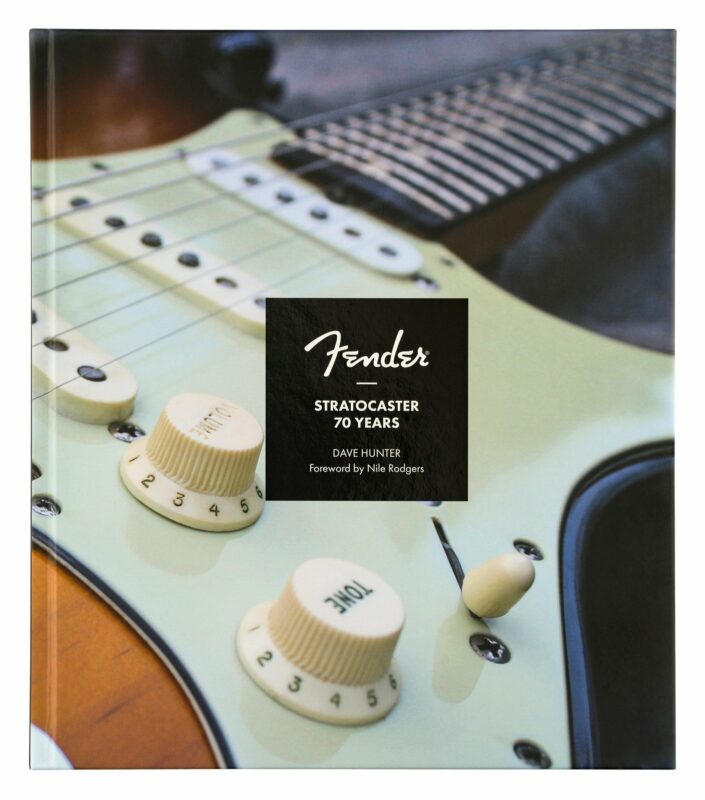

FENDER STRATOCASTER® 70TH ANNIVERSARY BOOK

- Apr 15, 2024

PowerZone by GRYPHON DEBUTS AT AXPONA

- Apr 13, 2024